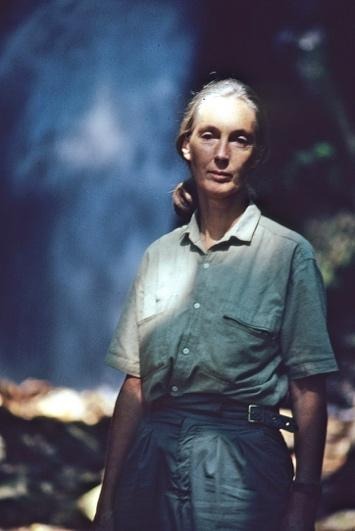

I first met Jane back in the 1980’s when she was the National Geographic cover girl. I was then working on a PBS series called The Mind, a sequel to the successful Brain series. My assignment in show one of The Mind was to take on the highest concept of brain function: what makes us humans so special… or not. So, my crew and I flew to Kilimanjaro, then chartered to Kigoma, then a wild four-hour boat taxi ride north to Gombe. Jane was waiting for us on the beach.

We hung out with Jane for about four days and in that time, she taught me to do chimpanzee pant hoots [PANT HOOT], and we heard stories of many chimps including David Greybeard whose trust she gained and who taught her so much. In short, this 26-year-old had gained the trust of a very aggressive contentious curious robust and sometimes loving pack of primates.

Notable was her revelation that chimps made tools. Previously Louis Leakey — her mentor and the father of modern human origins research — had defined man as the toolmaker: he called one such hominid homo habilis, the toolmaker. When she cabled him to say that she had seen a chimp using a stick as a rod to fish for termites, he famously wrote back, “Now we must redefine tool, redefine man or accept chimpanzees as humans.”

One night Jane and I sat on the beach of Lake Tanganyika looking at distant campfires in the Congo on the western shores of the lake. She and I were both drinking whiskies out of tin cups. We talked about the recent kidnapping of some of her students by Congolese rebels and then, into our second whiskey, she confided in me an astonishing family secret that someday I may write about. In any case, from that day on we were friends, seeing each other irregularly over the years.

From these encounters I concluded this about Jane:

- She dedicated her life to showing our deep connections to the animal world.

- She battled the stodgy scientific community by giving names not numbers to the chimps she studied and assigning real human emotions to them. At the time, that was scientific heresy.

- She never glorified the animals she studied, never claiming chimps were better than us, but much the same—waging war, killing recklessly, good and bad parenting, sharing friends for life, making enemies, cheating and loving.

- When she realized her scholarship would ring hollow if she did no more, she took on the greatest of all battles: protecting wildlands not just to ensure habitat for primates but to safeguard all their neighbors–from elephants to hyraxes.

- Deploring how scientific researchers tortured primates by testing them with painful and sometimes deadly serums, she campaigned to have them released from their prisons. And in giving primates freedom she denied herself freedom of her own, by living out of a suitcase 300 days a year, rarely enjoying her last days at her homes in Bournemouth, Dar es Salaam and Gombe.

- For Jane, the future resided in the aspirations of youth. She did so by creating a program called Roots and Shoots which today enjoys a worldwide membership and has led to extensive areas of the world being replanted, protected and loved.

- The secret of Jane’s addresses: she rarely cited statistics or figures. Instead, she told stories, of David Greybird and of a chimp called Bahati who when released from its cage of over 30 years rushed over to hug her. Stories were Jane’s magic.

- Jane was blindingly honest. When asked by a late-night comedian what was her favorite animal, she did not blurt “chimpanzees.” Instead, she said “dog.” And then she told the tale of her family pet in Bournemouth, a dog who taught her to love “the other life.”

- I don’t recall Jane ever calling out names, or creating an enemies list, or pillaring others. Instead, Jane talked of hope. She applauded high aspirations, never faults. In doing so, she set an example that lies in stark contrast to the dialogue we hear today, the venom spouted by public figures, mostly our leaders.

- Jane was an unlikely celebrity. She may have shaken a million hands, been photographed as many times. It never went to her head. She talked from the heart and listened to everyone, especially the young.

Shortly after our time at Gombe, I threw a party for Jane at the Explorers Club in New York. The aim was to raise money for African wildlife. She arrived early, dressed in a sun-bleached dress which she had clearly picked up in a secondhand store in Dar es Salaam and open-toed sandals. Plus a shawl. I asked her if I could get her something. She replied, “a whiskey.” We settled down to chat, minutes before our guests arrived. I asked her if there was anything else I could get her. She looked at the musicians tuning up. “Yes,” she said, “I’d love to dance.” And so we did, twirling around the tables decorated with miniature chimpanzees. And she wore a smile that would have been understood by humans and chimps alike.

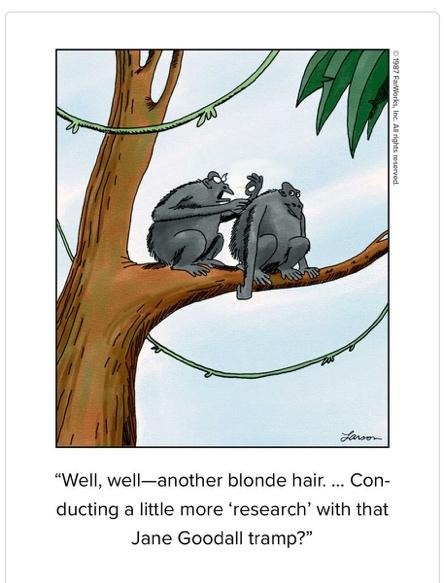

Lastly, Jane never took herself seriously. When Gary Larsen published a cartoon of her, the Jane Goodall Institute spluttered with outrage, saying it was disrespectful. Instead, Jane found it hilarious.

That was Jane.