Yonder: A Place in Montana

October 18, 2017In Full Flight: The YouTube trailer

February 1, 2018I thought I was done with undercover wildlife films until I received a call from Nanyuki, Kenya. My friend, photographer and fellow filmmaker, Karl Ammann, wanted me to help him complete his six-year film project, The Tiger Mafia.

Would I join him in Thailand and Laos to help him do the final bits on his covert film about the trade in captive tigers? On the crackling phone connection, he mentioned an improbable irony: even with tigers being voted the world’s most popular wild animal, they are down from a 1900 population of 100,000, to about 3000 today. And the worst, he noted ominously, is yet to come.

After grinding flights between Seattle, Seoul and Bangkok, I met Karl in Chiang Mai, Thailand. He and the talented Philip Hattingh a towering cameraman from Pretoria, allowed me five minutes to shower and change before taking me off to Tiger Kingdom—a kind of petting zoo for (so I presumed) unendowed Chinese men. Karl wanted me to understand the full import of this animal entertainment, having me picture the cruelty needed to subdue these exquisite predators to the hand—small hand, if you will—of their trainer. Training was one issue. The other was what happened after that–where the tigers went when their breeding days were over. While Phil filmed and Karl took stills, I suppressed my mounting rage.

Allow me to skip around to the mid-point of the trip, for what we saw (or didn’t see) may be all that counts. At the time we were spending two nights in a rustic lodge teetering over the Nam Poo River in the village of Naing Khiaw. What for me was captivating, for Karl was a staging post for a journey into the forests bordering Vietnam to the east. This mountain terrain is said to be the last stronghold of Laos’ wild tigers. When Karl was here six years ago he believes there were at least four or five wild tigers still at large. I am expecting the count to be far larger now.

For five hours we negotiate a rapidly deteriorating road, in search of news about these last wild tigers. The track, once engineered through German aid, follows hill top ridges as it disintegrates from road to track to pathway. Eventually, we transfer to a “Chinese water buffalo—“ a home-built conveyance, powered by a deafening diesel with wooden floorboards for seats. While the discomfort is near insufferable, the scenery is stunning– range after range of cascading mountaintops dissolving into distant blue. When evening overtakes us, Karl grills local Hmong villagers for news. They report that down the road others have been using land mines, modeled after those used in the Vietnam War, to kill tigers to sell to the Chinese and Vietnamese. There is an outside chance only one wild tiger remains, because, last month, someone reported seeing a single track. What, I ask? Only one wild tiger left in the whole of Laos?

Before taking up the thread of our journey, a quick word about Karl, for he is the reason I am here. The first word most utter when meeting him is “driven.” Even after forty years in the developing world, Karl retains his St. Gallen accent, as well as a bushy moustache and an unrequited fervor in exposing the inhumanity of the animal trade. Often he dresses in dark colors– perhaps to dupe crooks into thinking he is their equal in shadiness. Now in his sixties, he leads all at a run.

Karl, trained as an hotelier in the Swiss tradition, was initiated into the dark world of wildlife trafficking some thirty years ago when, while traveling on a Congo River steamer, he rescued two chimpanzees from certain death. Today “Mzee” and “Bili” continue to live the good life with Karl and Kathy Ammann. The chimps even have a television set of their own, their favorite show being Wimbledon (“Something about women players’ grunts excite them,” explains Karl). The Ammanns are so dedicated to their pets they have set up a trust fund to provide them with lifetime care, should they outlive their “parents.”

Chimps were Karl’s entrée to the world of wildlife crime. After he dropped the hotel business, he examined doctored export permits to followed felons trafficking chimpanzees and gorillas out of West Africa to Asia. After apes, Karl went on to investigate the illicit trade in ivory, rhino horn and finally tiger products. In each instance the demand side of the economic formula has led him to Asia where he has spent years chronicling the world of Asian cravings for wildlife. In China he found that eating rare animals is often a game of one-upmanship: the weirder an animal delicacy, the more it will fetch on Asian black markets.

Karl suppresses his outrage over animal injustice behind diligent fact checking and a growing conviction that C.I.T.E.S. (the Convention for the International Trade In Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), designed to protect the wild, is now part of the problem, even supporting criminal commerce in wildlife.

Back to my start. After leaving suspicious “Tiger Kingdom,” we drive northeast through Thai rice paddy fields to Chiang Saen. Just beyond, the road stubs out at the Mekong River, wide, brown, and abuzz with long-prowed vessels doing a brisk trade in contraband. Having risen on the Tibetan Plateau, this storied river here forms the boundary between three countries—Myanmar, Thailand and Laos: in other words, the Golden Triangle.

Here is where our journey goes wacky. Having crossed the Mekong to enter Laos—sort of– I step into a dark, surreal world. We are now in Kings Roman, a 100 square km “special economic zone,” leased from the Laos government for 99 years. “Special” is all about Chinese tastes; “economic” because the zone provides its number one tenant, kingpin Mr. Zouvit ZhaoWei (or Souwit or Chavvey, depending on who whispers his name) unsupervised revenues from gambling, prostitution, tiger farming and, most productively, the sale of amphetamines trafficked out of Myanmar. We found his home heavily guarded, fortified especially against journalists carrying cameras or notebooks.

On which planet have I landed? The casino out-kitches Las Vegas for its brightly illuminated exterior Roman Emperor statuary, and its interior for its grand staircase and stale tobacco smell. Nearby, the equally grand brothel resembles Le Petit Trianon. Inside (yes, we could not resist a look) the painted ladies sashay up staircases and along corridors, batting eyes from gold-filigreed bedrooms. In a conference room, a group of Chinese punters plan an orgy.

Kapok Garden, Kings Roman’s only hotel seems to be an annex to the bordello. Throughout our two nights in these “no star” accommodations we hear shouts and giggles, doors slamming, bottles crashing and one unfortunate client puking.

As far as I determine Karl, Philip and I are today the sole westerners in all Kings Roman (the only others who I know to have dared a visit are researchers, Esmond Bradley Martin and Lucy Vigne). Kings Roman is not for tender western hearts; it is for Chinese revelers, hell-bent in search of freedom from constraints—and laws.

On night one we see a tiger pacing a cage, abutting a Chinatown restaurant where he will be main course for an astronomically expensive banquet. In the morning, we cross a plastic-strewn field, crawl through a fencing to discover heavy cages, each containing pacing tigers—23 in all. An accommodating keeper, primed by thousands of kips (the local currency is 8000 to a dollar) introduced us to his wards, explaining that as soon as a female gives birth, the cubs are wrested from her (in the wild, tigers nurture their cubs for up to three years) and transported to the private zoo of the “Big Man–” Mr. Zouvit ZhaoWei. This is called “speed breeding,” since the female is forced to resume cycling and thereby prepare herself to be bred again. Some tigers give birth to several litters in a year. Here, cubs are for amusement, adults for mating, and the oldest for banquets.

In the casino, tiger bone is available for purchase, and in a nearby market patronized by weekending Chinese, we are offered tiger wine and tiger cake, all produced from floating fat in cauldrons of congealed bones.

Karl understands caveat emptor, appreciating that the Chinese are into tiger wine and the Vietnamese tiger cake. Tiger bones have become a medium of deception, even with Chinese criminals loving to dupe their own countrymen. Some of the tiger bones, tiger wine, tiger cake for sale are fake; others are lion bones, acquired at a steep discount from dealers in South Africa.

Three hours east we come to another “S.E.Z.,” this one, Boten, located under mine tailings and against the Chinese frontier. Unlike Kings Roman, there are no clients are visible. At a glittering duty free shop, sparkling with Givenchy and Chanel, salesgirls play games on their Samsungs, with nothing else to do. Down the road, the guard at a jade emporium bars the door to us, for reasons that remain unclear. Even without noticeable evidence of demand, developers appear undeterred. Heavy machinery churn the earth into a grid of streets, with cranes laying out the first floors of skyscrapers, and billboards advertising a hillscape of condos vomiting dollar bills.

To lure Chinese buyers to Boten, these developers will have to conceal a dark past linked to our hotel, the only one in town. By now, we are used to dumps and this is no exception– broken door locks, dismembered bathroom sinks, and a highly hostile concierge. But our hotel is more than a case of shoddy management. The story goes that over the course of several years there have been 60 gamblers who could not pay their debts to the drug lords. As punishment, they were marched up the stairs of our hotel and tossed off the roof to their deaths.

All is Armageddon until we climb a hill to a patch of ground leveled to make way for Boten’s national theater. It is framed by Tara-like columns and illuminated by klieg lights. The effect is a complete disconnect from the wasteland below. In the square by its entrance, there are four chained Asian elephants, approachable and ready to be nuzzled by an American. But then their mahouts look up, having heard the throb of diesel engines, screech of brakes, grind of doors. 22 buses are now disgorging over 500 middle aged and elderly Chinese passengers who have traveled many hours for tonight’s entertainment.

My befuddlement is complete when out of the theater 30 sequined women, batting eyes, flaunting poitrines, rolling hips slink out to join the crowd. All the women are knockouts.

I am completely mistaken. These are not women but a troop of “lady boys,” Thai transgenders, confected with make-up and setting my identity compass spinning wildly. Lady boys, with their overt but denatured sexuality are strictly forbidden in China. The audience, intoxicated by the shameless illegality of it all, goes nuts. One man asks a lady boy for “a feel,” and one timid husband goes screaming from an unwanted advance. The music intensifies while the elephants shift weight, one foot to another, perhaps also confounded. I feel sad for these creatures for I have learned they are here in detention as they await a sale to a Chinese circus or safari park where, almost certainly, they will be put on display, rented out for rides. Naturally, any such international sale would be in contravention of C.I.T.E.S.’s mandates, but, by now, who cares. Vive Boten!

The show, “Cabaret Excellente,” is, to my surprise, polished stagecraft—pulsing music, lavish karaoke, mistaken identities and a triumph of lilting, head-swaying bodies. This is not what I expected in a “special economic zone” where elephants, tiger parts and amphetamines serve as currency.

On our wild drive south from Boten, another surprise awaits. We stop on the roadside to watch two Chinese men in undershirts blow torching the corpse of a creature that, at first, neither Karl, Philip, Fong nor I can identify in its fricasseed state. It is about four feet long, with a distinct heavy tail and a narrow head. Only later, when Karl gets onto the Web, we learn it to be a binturong—sometimes known as a bearcat. This mammal is related to Asia’s palm civet, and lives high in the forest. Few zoos are lucky enough to have one (San Diego being an exception) and not surprisingly, across their range, they are classified as either vulnerable or endangered. Once again, it comes as no surprise the Chinese love a good illicit meal.

Later, in a market Karl finds a large cane (or bamboo) rat, secured by a harness, on sale. Karl does the right thing: he forks out a wad of kip for the rodent, and outside the village he releases the frantic fellow, who snarls his way up an escarpment and flees for cover. Godspeed…

We spend part of our long drives pondering the riddle why the Chinese engage in this all-out war against the wild? How can a culture built on Buddhist and Taoist principles of non-violence suddenly turn foe to nature? Some of us wonder whether the behavior is a hangover from years of deprivation under Chairman Mao who, during the Long March, Cultural Revolution and Great Leap Forward exterminated whole swathes of China’s population and then forced survivors to endure enormous deprivation. A generation still recalls having to eat grass and dirt. Now, with money to burn and freedoms galore, it is China’s turn, to turn the tables on nature. And so in China, its neighboring countries and throughout all the newest territories where the Chinese export cheap infrastructure and labor, nature is theirs to devour.

Laos is not only about putting the exotic and endangered on dinner plates. The next day, while boating down the Nam Poo River we find our way blocked, after two hours, by a formidable dam, just completed. It is one of 80 dams China intends to build in Laos on the Mekong and its tributaries. Fong explains that the Chinese, emboldened by Laos’ lax environmental rules, intend to make his country “the battery of Asia.”

Before arriving at the most beautiful of all Laotian towns I must pause to gross you out with the world of Asian comestibles. After that, I promise to move on.

For those wanting to buy ne plus ultra coffee, then kopi luwak, or civet coffee, is for you. It is grown alongside breeding facilities for Asian palm civets. Apparently, these beautiful wild cats are enraptured by coffee beans, which they consume with gusto. Accordingly, the dung of these civets is composed almost exclusively of digested beans, which are then collected to make this pricey blend. Kopi luwak: try it.

Bear bile farms: this one is serious. Laotians breed Asiatic brown bears for the Chinese market. Each bear is forced to spend its lifetime in a cage so small it cannot stand. An incision near its liver is left open so every day keepers can “milk” its bile, inflicting unimaginable pain (they howl throughout the operation). Even though bile could be replaced with more effective modern medicines, the Chinese cling to tradition, treating liver and gall bladder conditions (like hangover) with bear bile. Even now there are some 12,000 bears in captivity, mostly in China.

Now for some beauty. Situated on a peninsula formed by the Nam Khan and Mekong Rivers lies Luang Prabang, possibly the most attractive town in all Laos. Until 1975 it served as the country’s royal capital. Here, I must say, I felt at home. While Karl and Kathy (just arrived from Bangkok), were able to find the last room at a trendy new hotel and Phil settled into a boarding house overlooking the Mekong so he could fly his drone, I lucked out at a repurposed royal home, tucked between two Buddhist temples. It seemed to be at the center of all that matters in Luang Prabang. At 5:30 every morning I walked four blocks to view 100 Buddhist monks, clutching rice bowls, begging for alms. This ceremony was followed by the morning market, which shut down traffic on the street south of the hotel. By evening, I was ready for another flurry of retail at the night market, which effectively closed off the city’s central artery to the north.

In Luang Prabang there is no moment in the day when street vendors are not flogging silk shawls, woven handbags and elephant trinkets. If you have to travel about town in a tuk-tuk so be it. I found walking preferable. How else to evaluate restaurants, count massage parlors, torment pushy vendors and smell sticky rice? And then there are the illicit items, usually not at street level but under glass in antique shops off the main drag. Here Karl and Phil covertly filmed rhino horn, elephant hide, African ivory, helmeted hornbill horns (endangered of course), pangolin scales, tiger bones, tiger wine, tiger cake and shelves of bear bile.

Every night, to the sound of monks announcing curfew, we found a new restaurant to test the crispy fish and rice and enumerate the success and failures of the day’s shoot—sharp undercover close-ups of a storeowner boasting about the quality of his tiger bones, and a drone fly-over that failed because of wind. Investigative films are anything but predictable.

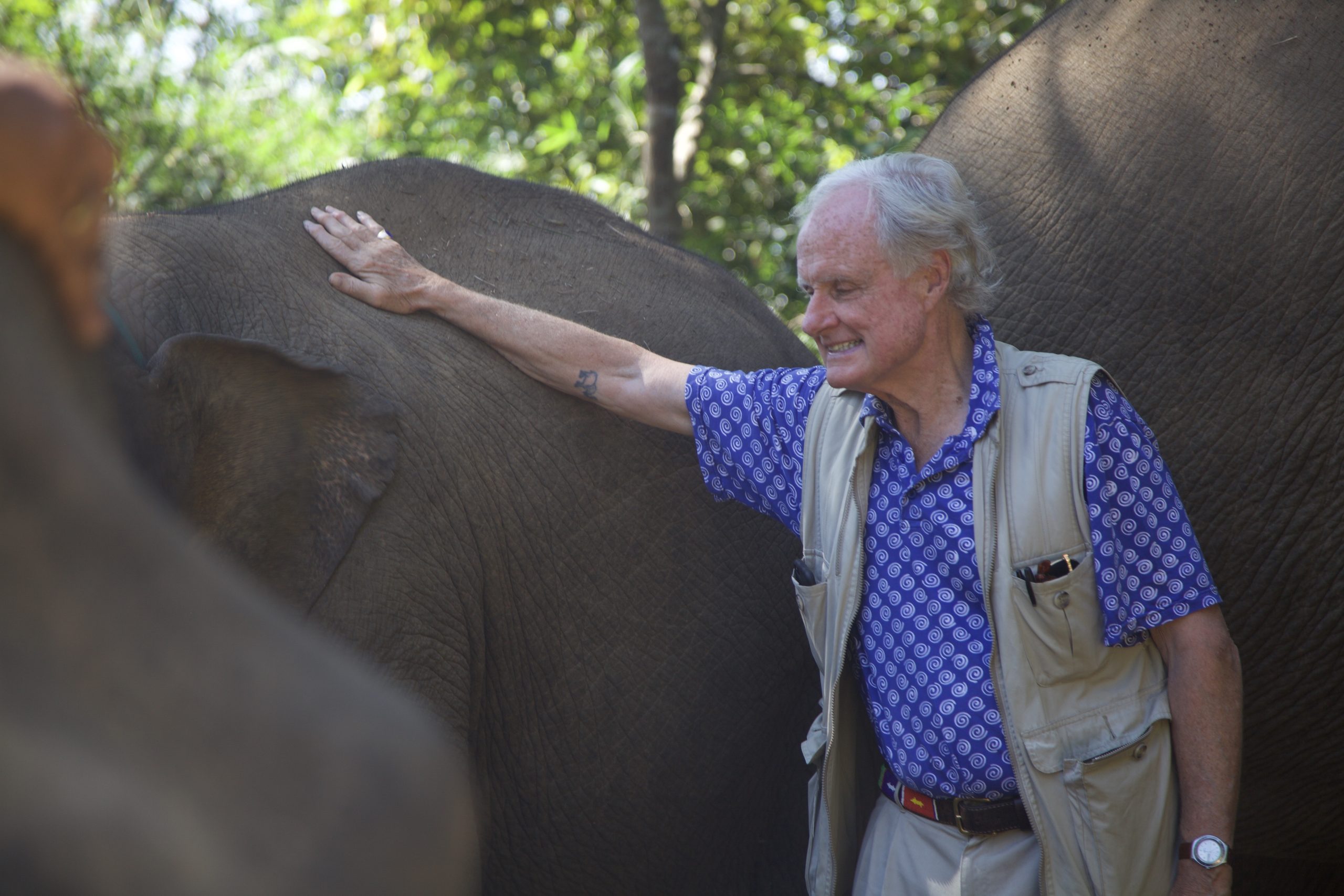

We spent our two days in Luang Prabang going out to meet elephants—first at the popular Tad Sea Waterfall Elephant Camp where Chinese tourists pay for elephant rides, and western school kids strip down into bathing suits, sit on elephant backs and get wet and muddy together.

I suspect few visitors will drive two hours as we did to visit a more remote elephant reserve— this one a temporary holding area for the homeless. Here we mingled with 16 elephants (two of them calves), in animal limbo, because of an unconsummated sale to buyers in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. The deal was thwarted, for the moment, because it constitutes an infraction of C.I.T.E.S. rules. But will that matter in this realm of shady deals and shoddy regulations? Probably not.

Later, in motorbike-crazed Vientiane, the capital of Laos, we heard from several parties that the international elephant deal would indeed proceed, rules be damned. Still, no one is certain of the roadblocks. As of this writing, the elephants await their fate, while their mahouts devotedly take them to water and, when the occasional visitor shows up, induce them with bull hooks to lower themselves to their knees, entwine their trunks or blow water into the air.

What Karl found most ironic was that, of all habituated wild animals, elephants are among the few that will prosper if returned to the wild. There they can mate with wild elephants and live off the forest. Wouldn’t that be wonderful? Who knows. Maybe in Laos, miracles happen.

On my final day, we left Vientiane and drove three hours east to Pakxan for a final installment in the world of wildlife crime. Said to be the hometown of Vixay Keosavang, the Pablo Escobar of the Laotian wildlife trade, Pakxan is a fairly nondescript Laotian community of wide streets and businesses, hovering precariously between touch-and-go and abandonment. The only anomaly is a collection of ostentatious homes protected by gilded gates and fences. There is little doubt how their owners came by their wealth in this hardscrabble town.

On our way into town we stopped at a roadside brothel for a coffee and a reconnoiter. Across the road we knew lay an animal farm concealed in thick cover, filled with hundreds of macaque monkeys, for assignment to Chinese research labs, and 233 tigers, awaiting transit for breeding or consumption. We positioned the car in a turn-off near a school so Phil could fly the drone for an inspection. So not to attract attention, we left him to it, as he overflew the many cages and birthing boxes. In the end: a disappointment with keepers and tigers laying in shade, invisible to our camera.

The rest of the day we spent searching for the tigers’ owner. When Karl knocked on the door of one mansion, he was denied entry. Later, we surveyed the abandoned car lot of its proprietor who had conveniently left town. We spent all day gathering evidence against Vixay Keosavang. In the end, we found many leads but few resolutions– rather typical for this sort of work.

That night, while Karl and Phil journeyed to China and Vietnam, I headed home for Thanksgiving, boarding a plane in Vientiane, with stops in Bangkok, Hong Kong and Seattle. All the while I pondered what I had seen in Laos, what driven Karl, wise Fong and the great people of Laos had helped me understand. The future of the tiger still eluded me. On the flight, I drew up a few questions and some ill-formed conclusions:

- Why is it that those who believe in Buddhism (“wisdom, loving-kindness, compassion, renunciation of craving”) and Taoism (“vegetarianism, naturalness and non-violence”) are now more interested in consumption, violence and nature’s exploitation?

- How can a government knowingly condone crime?

- How can a people neglect the long-term national good in favor of short-term personal reward?

- The Internet, the cell phone and courier services are gods and devils– instruments for good, engines of mass destruction.

- Laotians often share with other developing countries an indifference to wildlife. They may be thinking that for us to survive, why should we care about the needs of an animal?

- After much hardship, the Chinese now feel they have the right to party.

- Across the world from Laos to Africa, the Chinese are the new imperialists, dangling the promise of infrastructure in exchange for free reign with commodities.

- Whether in Thailand, Laos or China, hope for change falls to younger generations. But, if they are the solution, is there enough time?

- China and other Asian nations do not take kindly to being scolded, or shamed, by Westerners.

- International wildlife bodies are investing their intellect and treasure in eye-catching projects that, in the end, may prove to be no more than window dressing.

- Partnerships may be the only way to affect change. Potentially, in China the rich and powerful could be the perfect allies to save the wild and slow crime.

- What endures? Ghostly monks at dawn in Luang Prabang, haunted looks of captive elephants, compulsive pacing of caged tigers, and a few enduring lines from William Blake: “Tyger Tyger, burning bright, In the forests of the night; What immortal hand or eye, Could frame thy fearful symmetry?”